by Yinka Elujoba

The old woman sat on the road with a song in her mouth. It was a song about fallen breasts. I watched a fly dance around her lips as she sang. The fly was the only swimmer in her forgotten melody. She ignored it. I walked towards her and sat on the road too.

“Who are you?” she asked.

“My name is Yinka. I go around cities, collecting stories from little people.”

She laughed, her brown teeth like newspapers from decades of storage.

“Little people?”

“I’m sorry if the name sounds condescending—”

“No. No. ‘Little People’ is such a perfect name.” she laughed again. The newspapers fluttered beautifully in her mouth.

“You think it is?” I asked.

“Yes. Every human at their centre is little. Our wants at that centre are little things—food, and the chance to laugh sometimes.”

“You laugh so easily,” I said.

“Ha. You’d be surprised at the kind of laughter you’ll find when sorrow is all you have.”

“Tell me about the song you were singing,” I said.

“That song? I first heard it on the lips of a dying woman in a hospital where I worked as a nurse—”

“You were a nurse?” I asked. Her face became a stone. The newspapers disappeared between her lips.

“Yes I was. Many years ago at the General Hospital. The woman was a cancer patient, you see? You know cancer, don’t you? Cancer is a trickster. It deceives the cells. It lies to them. It tells them they can be more than they are.”

“Teach me the words of the song.” I said.

The woman shook her head. The veins of her neck twisted into tiny knots.

“The song has no words. The words of the song change, depending on what the day holds.”

The woman noticed I had raised my eyebrows in disbelief.

“I had your reaction when the cancer woman told me her song had no words. I memorised the words from the song she sang on the day she died. After I came to this place, I sang the song everyday with the same words. Then one day, a train came. I saw the people pour out of it. In their faces were new words for the song. That was the day I believed the woman.”

“How often does the train come?” I asked, studying the rail tracks across the road.

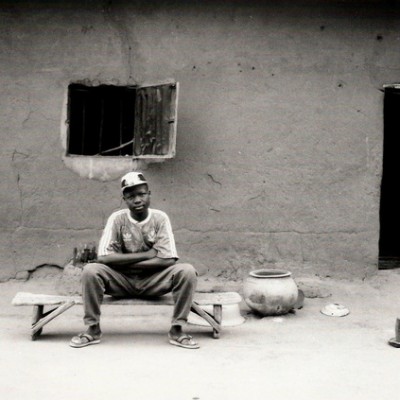

“It has not come since then. I believe it came just to drop the little boy. They called him ‘Bellybutton’.”

“Bellybutton?”

“Yes. He had a bellybutton the size of a pear. He used to stay right across me on the rail tracks. Early on Saturday mornings he would buy me hot pap and akara from a woman down the road with money he made from begging during the week.”

“He must have been such a kind-hearted little boy.”

“Ah. Yes he was. But kindness always finds kindness. Months ago, a rich man came from Lagos and took him away to school there.” The newspapers returned as she spoke of the boy.

“What about you? Tell me your own story.” I said.

The woman looked into my eyes. Her eyes held an inaccessible promise. A promise that would never be fulfilled.

“You know how it is that the rag was once a beautiful cloth. This cloth was a beautiful nurse once. I gave myself to nursing. The only thing I lived for was watching patients recover from their illnesses. I worked overtime voluntarily. It meant more time to treat more people. I never considered marriage, you see? It could never have worked.

If I had to choose between my work and a family, I would choose my work.”

I watched her as she spoke. Her fingers, long and thin, pierced the air. The tips of her nails were crooked. I knew she had been scratching the road with them.

“I belonged to the world for long, but nothing in the world belonged to me. Then when I was fifty, they rushed a boy into the emergency ward. His parents had been with him in a car accident, but he was the only one who survived. The left part of his face was burnt from a fire in the accident. I became attached to him immediately. I stayed beside him day and night, and painted the scar on his face on every piece of paper I found. I knew how many times he coughed. How many nightmares he had. All of the words he said in his sleep. When he woke and cried for his mother. I was all he had, and for the first time, something in the world belonged to me.”

“So what happened?” I asked.

“He began to get better. His coughs reduced, and so did the nightmares. Then one day, blood poured out of his nostrils. He opened his mouth and it was full of blood. The doctors said an internal organ had torn in him and he was bleeding too fast. He died, drowned in his own blood.”

The woman sighed and sang her song again.

“Earth played a fast one on me. It gave me something to own and took it away. So I sold all that I had and left the job at the hospital. I came to sit on this road, to sit on Earth. I am waiting for Earth to come take me.”

I looked at the woman and closed my book.

“What will you do with this story?” she asked.

“I will write it where people can read it. In a book.” I said getting up to leave.

The old woman pulled me back by the hand, laughing.

“What about you? What is your story?”

Yinka Elujoba studied engineering at Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife. Whenever he is not writing stories, he heads Design at Fooshia.

Awesome!!!!!

Hmmmm. Life doesn’t give a damn and would say ‘I could care less’. My advice is that we make of it what we can and just hope our stories can be heard and be told too

Damn! It’s so weird how sometimes things seem so well planned and in sync only for the universe to remind you we are all accidents from millions of years of trial and error.

Brilliant! Yinka has a rich mind.

A good one, Excellent. Author has such an active imagination.